|

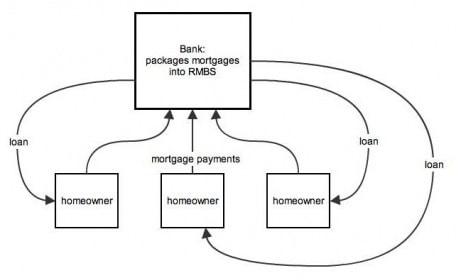

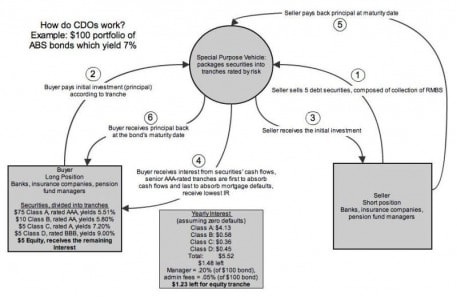

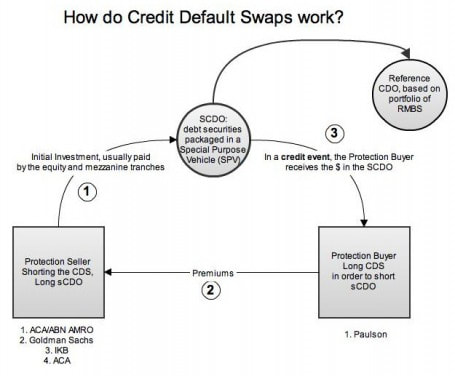

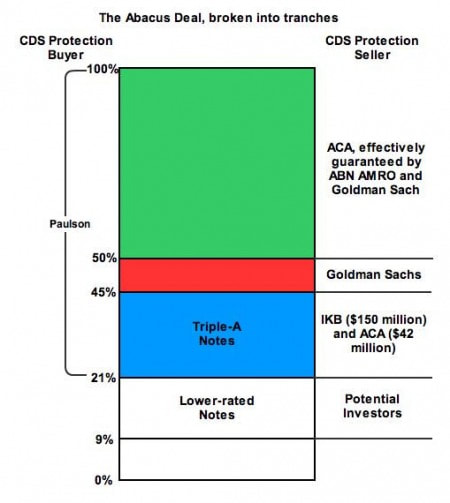

In the last few weeks, what’s been going on with Goldman Sachs has shaken investor confidence in the financial markets. Like many other students, I’ve followed the news about Goldman with curiosity, but I’ve been puzzled by such terms as “collateralized debt obligations” and “credit default swaps”. Weeks of research later, here is my explanation of the SEC complaint against Goldman Sachs, written specifically for non-financial experts like me. I hope you enjoy. First, an Introduction to the SEC Complaint and Some Key Players The SEC website says: SEC Charges Goldman Sachs With Fraud in Structuring and Marketing of CDO Tied to Subprime Mortgages (April 16, 2010) “The SEC alleges that Goldman Sachs structured and marketed a synthetic collateralized debt obligation (SCDO) that hinged on the performance of subprime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS). Goldman Sachs failed to disclose to investors vital information about the CDO, in particular the role that a major hedge fund played in the portfolio selection process and the fact that the hedge fund had taken a short position against the CDO.” I’ve underlined and bolded some terms/players that will be important in understanding the Abacus transactions, and defined the easy ones here: SEC: The Securities and Exchange Commission, created in 1934, holds primary responsibility for enforcing federal securities laws and regulating the securities industry. Goldman Sachs: a global investment banking, securities and investment management firm headquartered in New York City. GS&Co structured and marketed ABACUS 2007-AC1. One of Goldman’s Vice Presidents, Fabrice Tourre, played a key role in the Abacus transaction. Investors -IKB: a commercial bank headquartered in Dusseldorf, Germany -ACA: third party with experience analyzing credit risk in RMBS -ABN AMRO: one of the largest banks in Europe during the relevant period Major hedge fund: Paulson & Co. Inc. The following two are more complicated will be broken down soon. Synthetic collateralized debt obligation (SCDO) Subprime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) Now, hopefully you all have a basic understanding of the major players involved in the Abacus transactions. I next want to introduce Residential Mortgage Backed Securities, Collateralized Debt Obligations, and Credit Default Swaps. Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) Let's start with RMBS. Essentially, RMBS are groups of mortgages that banks package together. What happens is that banks give homeowners loans to purchase their houses in exchange for fixed mortgage payments. Every month (or year, however long the payment period is), homeowners pay mortgage payments to the bank, which provides the banks with a source of cash flow. Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) Now, I want to address CDOs, or collateralized debt obligations, which are only slightly more complicated than RMBS. CDOs are basically bonds: one bank borrows money from another bank in exchange for interest payments and the principal amount due back at maturity. They rely upon the cash flow generated from RMBS to pay the interest payments, and eventually, to pay back the principal. So how does it work? First, the seller, or bank, sells a collection of RMBS to a buyer (1). These assets (or collection of RMBS) are stored in a Special Purpose Vehicle, which then separates the RMBS into tranches (risk levels). Depending on the amount of risk he wants to assume, the buyer then selects the types (tranche and amount) of securities he wants to purchase from the SPV (2). In our example, listed below, there are five classes (tranches) of securities that a buyer can invest in. Class A securities, rated AAA, yields the lowest interest rate (5.51%), but are also the safest investment because their interest and principal is paid first from the RMBS cash flow. These Class A securities are in the Super Senior tranche. Class B securities are also in the Senior tranche; as you can see in the chart, they are rated AA, with an interest rate of 5.80%. This interest rate is higher than the Class A interest rate because the Class B securities are inherently more risky. As you go into the mezzanine tranches (Classes C and D) you can see that the interest rate gets higher: this is because the lower classes are taking on a lot more risk. There is more risk because the underlying asset (RMBS) may include more debtors that may not be capable of making their mortgage payments monthly. Once the buyer decides what type of security to invest in, he pays his initial investment to the seller (3). In fixed increments, the seller then pays the buyer interest on his investment, according to the tranche properties discussed above (4). Now, let's examine the interest payments carefully here. In this example, the CDO is a $100 portfolio of RMBS that yields 7%. This means that given yearly interest, the CDO would yield $7 per year. To come up with the interest paid to each tranche, multiply the amount of the investment (Class A: $75) by the interest rate (for Class A: 5.51%) to get the interest per year (Class A: $4.13). For Class B, that would be an initial investment of $10 * an interest rate of 5.80% to get $.58 interest/year. For Class C, that would be $5 * 7.20% to get $.36; for Class D, that would be $5 * 9.00% to get $.45. When you add up these totals, you get $5.52, leaving $1.48 left to pay for management and administration fees and to pay the equity tranche (($7.00 yielded in total interest) - ($5.52 paid to senior and mezzanine tranches) = $1.48) . In our example, the management fees are $.20 (.2% of $100) and the administration fees are $.05 (.05% of $100), so that leaves $1.23 for the equity tranche ($1.48 - $.25). However, it is notable that our example is based on a zero default rate, which rarely happens. Even in good times, homeowners are going to default on their loans, meaning that the portfolio of $100 may end up going to $95, if 5% of the mortgage payers default. And then that doesn't even begin to hint at the problem of say, 25% defaulting on their mortgages, which would be more realistic in the housing crisis time period. Then, the portfolio of $100 would be down to $75, which would create problems when interest needed to be paid. $75 * 7% = $5.25, not enough to even cover the interest past Class C. And what would happen when the principal needed to be paid back? The $80 would only cover the Class A principal and 1/2 of Class B's principal, leaving Class C, D, and the equity tranche completely worthless. Starting to get the picture? When the housing market fell apart in 2007, many homeowners began to default on their mortgage payments, so many that the value of many CDOs were going to zero. Banks lost millions, if not billions. Now that we have finished analyzing the interest payments, we can review the final parts of a CDO. At the maturity date, the seller pays back the principal (5), and the buyer receives his principal back (if there is any money left) (6). Credit Default Swaps and Synthetic CDOs The next question is, how do synthetic CDOs work? Well, synthetic CDOs operate through financial contracts called Credit Default Swaps (CDS). In CDS, there are two sides, a protection buyer and a protection seller, each who have a different perspectives on the reference CDO's future performance. As we discussed in the CDO explanation, CDOs fail when the assets that they are based on -- in Goldman's case, RMBS -- fail, or go into default. Now, in a CDS contract, the protection buyer buys insurance on the CDO because he believes that it is going to fail for whatever reason (in Paulson's case, he selected RMBS for the Abacus reference CDO that were composed of homeowners in CA, NV, FL, and AR, states with quickly appreciating housing markets, and of homeowners with low FICO scores). The protection seller believes that the CDO's reference portfolio is going to be okay and that the homeowners will continue to make their mortgage payments, so he sells insurance. This is sort of tricky -- the protection buyer goes "long" on the credit default swap because he wants to be negative, or "short", on the reference CDO; the protection seller goes "short" on the CDS because he wants to be positive, or "long", on the reference CDO. (The terms "short" and "long" don't really matter, but I have included them for finance buffs who like those terms.) What this means is that the protection seller is going to put an initial investment into a SPV, much like in a regular CDO. The protection buyer is going to then pay the protection seller "premiums" in fixed increments. Finally, if a credit event takes place (if homeowners don't make their mortgage payments and the reference CDO fails), the protection seller is responsible for covering the protection buyer's loss. As we saw in the CDO example, many CDOs have the potential to lose all of their value very quickly if homeowners start to default, and thus CDOs are very risky. Credit default swaps compound this risk: now, not only do the investors in the CDO have risk, now those in the CDS have risk too. So what actually happened in Abacus 2007-AC1?Step 1: Goldman Sach’s product correlation desk was created in late 2004/early 2005 to structure and market a series of synthetic CDOs called “Abacus”. Their performance was tied to underlying assets called RMBS. Fabrice Tourre worked as a Vice President on the structured product correlation trading desk, and was primarily responsible for the structuring and marketing of Abacus 2007-AC1. Step 2: Paulson & Co. Inc. saw an opportunity to short the housing market. It created two funds, called the Paulson Credit Opportunity funds, which took a negative view on subprime mortgage loans by buying protection through CDS on various debt securities (shorting the SCDO). Basically, Paulson believed that a large number of people would default on their home mortgages, enough to make the underlying RMBS in the CDO's reference portfolio fail. If the RMBS failed, Paulson would make huge profits. Step 3: Goldman Sachs and Paulson discussed the proposed transaction. Paulson identified various BBB-rated RMBS that it expected to experience credit events (fail), and asked Goldman to help it buy protection on these RMBS through the use of CDS. The Huffington Post uses a particularly apt metaphor to describe Paulson’s actions: “When you buy protection against an event that you have a hand in causing," said a structured finance expert, "you are buying fire insurance on someone else’s house and then committing arson.” Step 4: Goldman Sachs knew that it would be near impossible to place a synthetic CDO if they knew that a short investor, Paulson, played a big part in the portfolio selection process. Instead, GS proposed that a third-party collateral manager, ACA serve as the “Portfolio Selection Agent” for a CDO sponsored by Paulson. ACA agreed. Step 5: Paulson and ACA worked on collateral selection process. Paulson identified over 100 BBB-rated RMBS it expected to experience credit events. The hedge fund favored RMBS that included a high % of adjustable rate mortgages, low borrower FICO scores, and high concentration of mortgages in AR, CA, FL, and NV, states that had recently experienced high rates of home appreciation. To simplify Paulson and ACA's interactions in choosing the reference portfolio, I have included this timeline.

Step 7: The Abacus transaction. The reference portfolio is created with input from Paulson and ACA (as outlined in Steps 1-6).

In conclusion, does the SEC have a case and how does the case affect Goldman Sachs stock? Hopefully now you've gotten a better understanding of what happened in Abacus 2007-AC1 and about the SEC complaint against Goldman Sachs. A lot of debate has been ongoing about whether the SEC even has a case. As I’ve outlined, ACA Management chose only 55 of Paulson’s original 123 RMBS recommendations, and added an additional 35 to the final portfolio. In this situation, does Goldman Sachs have an obligation to its clients to reveal that an investor looking to short the SCDO had a hand in choosing the reference portfolio? Regardless of any wrongdoing, illegal or otherwise, Goldman stock has been doing notably worse ever since the SEC case broke on April 16. Evidence? Shares of Goldman Sachs plunged more than 10 percent in just the first half-hour of trading after the suit was announced Friday morning (April 16). On the day, they closed down 13 percent, at $160.70, wiping away more than $10 billion of the company’s market value. Since April 16, Goldman shares have dropped roughly 23%. That's more than twice the decline of the benchmark S&P 500 Index. Below is a chart of GS stock for the last three months. As you can see, there is a precipitous drop right after April 16, when the SEC case was first announced. So will the decline in price of GS stock continue? Goldman Sachs reported that daily trading net revenue was $25 million or higher in all of the first quarter’s 63 trading days, which means that they made money from trading every day last quarter. Even after the allegations, Goldman Sachs is one of the strongest investment banks on Wall Street and primed to survive this scandal.

With that said, I'd like to conclude this monster blog post about a topic that has captivated me for the past few weeks. I hope you all have learned a little about Goldman Sachs and how collapsing investments in the housing market tore through the U.S. financial system. I definitely had fun doing the research. Sources CitedFull text of the SEC complaint can be found here: http://www.sec.gov/litigation/complaints/2010/comp-pr2010-59.pdf I used this site to create all of my charts: http://www.gliffy.com/gliffy/#d=2118702&t=CDO_2 The numbers I used in my chart explaining CDOs were taken from: http://seekingalpha.com/article/48283-how-does-a-cdo-work I referenced this blog to outline how Abacus worked: http://www.aleablog.com/abacus-for-dummies/ Further websites I utilized:

4 Comments

|

AuthorMelanie Gin, second year Business Economics & Political Science undergraduate student at UCLA, enjoys writing, consulting, stock trading, and playing Ultimate Frisbee. You can contact her at [email protected]. ArchivesCategories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed